Joseph Valentine Durden [known professionally as J. V. Durden] was a filmmaker who began his career working alongside key figures in the history of popular scientific filmmaking, including Mary Field and F. Percy Smith. His professional life saw him work in three different countries over the course of nearly four decades.

Durden was born in London in 1910, to Ruby Valentina and James Durden. In 1919, the family moved to Moresby in Cumberland, and in 1924 they moved again, this time to Keswick in the Lake District. Both moves brought Durden into close contact with the natural places that served as the principal subjects in his father’s work, who was a well-known landscape painter. Between 1924 and 1928, Durden was educated at Stowe School, a boarding school in Buckinghamshire, after which he spent a year at the Alpine College in Arveyes (Switzerland). At this time, photography stood alongside mountaineering as the young Durden’s principal passions.

Durden registered for an undergraduate degree at the University of London in 1929, initially studying Physics and Chemistry at the Royal College of Science (RSC), which was part of Imperial College. He later specialised in entomology and biology, studying under H. R. Hewer at Imperial College. He graduated with a Bsc in Biology and Applied Entomology in 1933. In 1934, he was the official photographer on a plant collecting expedition in Basutoland (present-day Lesotho) led by Helen Milford. Spending time in South Africa, he happened to see a Secrets of Nature film in Cape Town, and he was so impressed that he resolved to become a scientific filmmaker himself.

He joined Gaumont-British Instructional (G.B.I.), the company responsible for the Secrets of Life films, in 1935. Durden’s work focussed on G.B.I’s educational films in zoology, which were supervised by Julian Huxley and Durden’s former university tutor, H. R. Hewer. His film The Sea Urchin (1935) was awarded the top prize for a scientific film at the International Exhibition in Brussels in 1935. Although Durden had taken an interest in natural history photography from a young age, he likely learned many of his skills in stop-motion and cinemicrography from F. Percy Smith. For most of the 1930s, he made films for the GBI biology series, as well as contributing footage to Secrets of Life. Durden became an expert cinemicrographer, building on the techniques used by F. Percy Smith, and incorporating new methods as they became available, including the use of phase-contrast microscopy and colour cinematography. Durden was instrumental to the development of the first series of Secrets of Life released in colour, which were made using the Dufaycolor process and were released in 1939. The Kinematograph Weekly, on viewing these films, wrote that ‘the manner in which colour enhanced the interest was very evident’.

Durden appears to have defined the term ciné-biology, which served as a way to describe the multiple contributions that film could have on the practice and dissemination of science. For Durden, it was also an identity: he described himself as a ciné-biologist, and wished to be recognised as a ‘peculiar hybrid’, a scientist-filmmaker. In particular, Durden felt that the potential contributions that film could make in scientific research were insufficiently recognised. ‘That the film is not more widely recognised and employed,’ he wrote, ‘as a most valuable tool and method of record in the hands of the scientific fraternity, is a fact which has amazed and disquieted me for a long time.’

In 1938, Durden co-directed And Now They Rest (1939), a survey of the fading tradition of working windmills. He worked alongside Brian Salt, whose principal specialism was in animation: in this respect it was an unusual film to make for both directors. However, through his association with both Salt and Percy Smith, Durden is likely to have learned his skills in animation, which he put to use during the Second World War, when he worked at the Army Kinematograph Service (AKS), making instructional films for military training. In 1949, he wrote the script for Atomic Energy, which was awarded a BAFTA ‘Special Award’.

After the war, Durden established his own company, Photomicrography Ltd., which was geared towards providing specialist scientific footage for a range of clients. During this time he made a series of ten films for the Shell Film Unit (SFU), ‘Plant Pests and Diseases’. Led by Arthur Elton, a director committed to industrial and scientific filmmaking, Shell was one of the principal documentary film units in Britain, and continued to sponsor an extensive programmes of films at a time – the 1950s – when the film industry in Britain was experiencing difficulties. Durden’s films for Shell covered mostly entomological subjects, including the raspberry beetle, the apple aphis and the red spider, as well as one film about brown rot, a fungus affecting apple harvests. At this time, Shell was expanding its business by repurposing the by-products of petroleum refining, and this included the production of chemical pesticides, many of which were designed to kill the agricultural pests illustrated in Durden’s films. Durden was supervised by H.G.H. Kearns of the Long Aston Research Station, but overall was pleased with the freedom he was granted in producing the films and called it “a job after my own heart”.

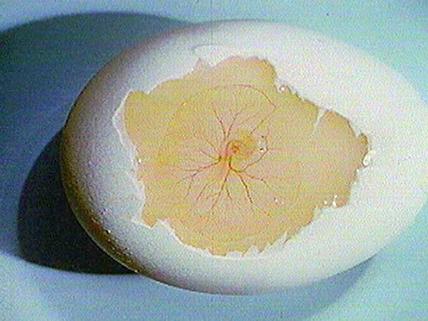

However, this situation did not last long, and after his contract was terminated by Shell, Durden found himself working freelance, unable to secure stable employment in the kind of laboratory-studio that he desired to lead. In 1952, he emigrated to Canada, where he helped to establish a Science Film Unit at the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), and produced several important films, including The Colour of Life (1955), a film about the maple tree, and Embryonic Development: The Chick (1953). These films showed Durden’s mature style, with a particular mastery in the use of colour for biological subjects.

However, Durden was dissatisfied with his position in Canada, and in 1962 he accepted a job at Educational Services, Inc. (later renamed Educational Development Centre) in Boston. Here, finally, Durden felt that he had at his disposal the necessary resources and institutional support to conduct his work properly. Driven by Cold War fears over the US’s perceived scientific inferiority, the National Science Foundation (NSF) was pouring money into science education in the 1960s, and Durden’s work benefitted from this stimulus. It was an NSF-funded initiative, the Developmental Biology Film Series, which arguably constitutes Durden’s biggest contribution to scientific filmmaking. Durden was the principal cinematographer for these films, which were supervised by leading scientists and were intended for advanced biology classroom work. These films had a powerful impact on the evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis, who used the films in her own teaching, and was even inspired to make her own research films. Margulis, who was still using the films in 2010, initiated a campaign to restore and digitize the films, calling her efforts “the most important contribution I have made to science in my lifetime”. The films were recently digitised and are available to view here.

Following his retirement in the early 1970s, Durden returned to England, where he died in 1998. Durden’s wife, Kathleen, had passed away in 1985. Together they had two children: a son, Christopher, and a daughter, Janet. The family donated Durden’s papers to the British Film Institute’s National Archive in London shortly after his death, where they are held in the Special Collections department. Durden’s collection is a unique resource for the study of the history of scientific filmmaking, spanning three countries and running from the 1930s to the 1970s.

This page was written using material available at the BFI National Archive, supplemented with notes and other primary source material kindly provided by Janet Hey.