Producers

Secrets of Nature and Secrets of Life were made by a wide range of individuals. Aside from nature photographers, cameramen and film producers, these also included scientists and teachers who acted as consultants. This page collects information about these individuals and offers links to explore more about them.

Harry Bruce Woolfe; Winifred Clara Cullis; Mary Field and Sir Edward James Salisbury. Photograph by Howard Coster.

© National Portrait Gallery, London

F. Percy Smith (1880-1945) was one of the most innovative cinematographers of the twentieth century. He was a pioneer of early nature cinematography. Described by one contemporary as a ‘wizard’, Smith mastered the techniques of microcinematography and fast-motion photography, helping him to create spellbinding images of microscopic animals or plants in motion. [Read more] Image: Mary Field and Percy Smith, Secrets of Nature (1934).

Mary Field (1896-1968) became the series producer of Secrets of Nature in 1929. Previously a history teacher, she joined the film industry as an historical consultant in 1925. Although she had no training in science, Field quickly proved herself to be a first-class film director, developing a unique style that fused education and instruction. [Read more] Image: Mary Field and Percy Smith, Secrets of Nature (1934).

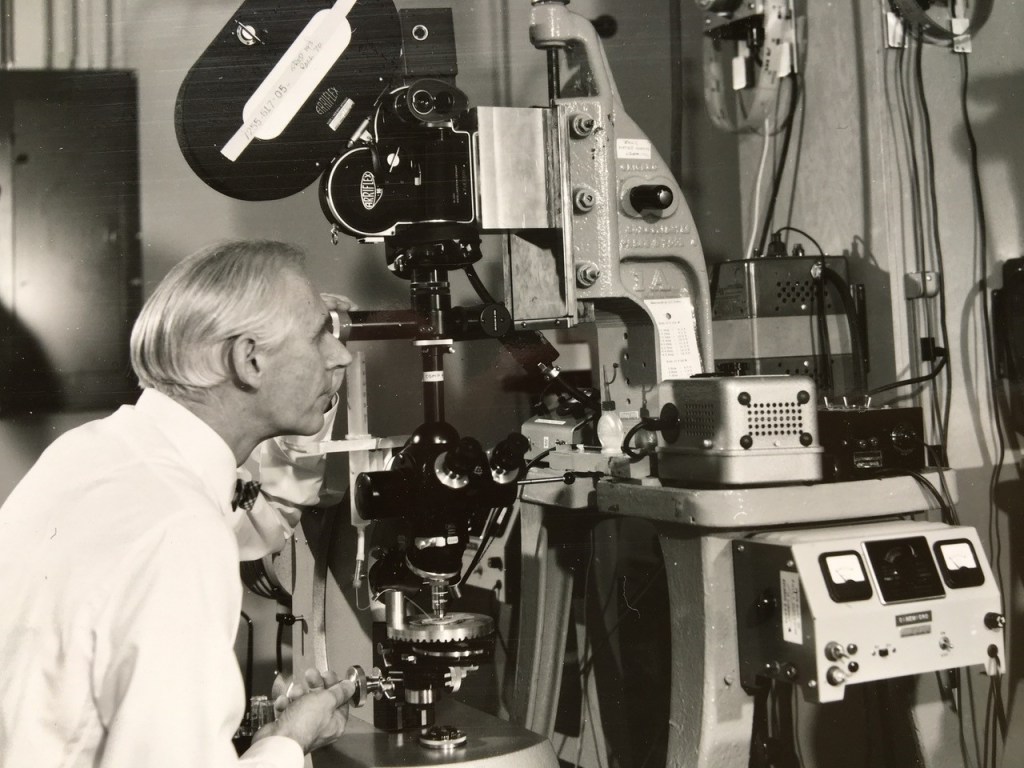

J. V. Durden (1910-1998) joined the Secrets team in 1935, after the move to Gaumont-British Instructional. Durden became one of the principal cinematographers in the Secrets of Life series, and rapidly adopted Percy Smith’s enthusiasm for laboratory-based films. Unlike Smith, Durden had trained as a scientist, having gained a degree in Biology and Entomology at the Royal College of Science. Spending time in South Africa, he happened to see a Secrets film in Cape Town and resolved to make scientific films himself. [Read more] Image: with permission from Janet Hey.

Harry Bruce Woolfe (1880-1965) was the managing director of British Instructional Films, and later Gaumont-British Instructional, the two production companies responsible for producing Secrets of Nature and Secrets of life. Bruce Woolfe produced a number of World War I films before embarking on the Secrets series. He devised of the idea behind the series after reading Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selbourne. Bruce Woolfe was a keen imperialist and a fierce promoter of his own films. He sat on several influential committees, including the Federation of British Industries and the Colonial Office’s Film Committee. Image: Mary Field and Percy Smith, Secrets of Nature (1934).

Margery Locket (1886-1971) was the Educational Manager at British Instructional Films, later becoming Educational Representative of G.B.I. Films. Locket liaised with teachers, educational authorities and other institutions, seeking their collaboration in the production of educational films, and convincing them of the value of the cinema in the classroom. She was instrumental in ensuring that the Secrets of Nature films were used widely in audience experiments across the country. Locket also delivered talks on the BBC about educational films. Image: British Newspaper Archive.

Oliver G. Pike (1887-1963) was a pioneering naturalist photographer who specialised in ornithological pictures. Alongside Percy Smith, he was one of the principal cinematographers for the Secrets , producing footage for them between 1921 and 1947. Pike was active in the field from the very beginnings of natural history film, and his silent films In Birdland (1907) and St Kilda, Its People and Birds (1908) were ground-breaking ornithological films. Image: Mubi.

Phyllis Penn Bolté (1901-1935) was F. Percy Smith’s laboratory assistant. She lived together with the filmmaker and his wide, Kate Smith, at their home in Southgate. In this picture she is demonstrating the function of a ‘plant machine’, a clever contraption which enabled footage of a plant’s growth over time to be captured automatically. After a visit to F. Percy Smith’s studio in 1934, the journalist Mary Benedetta described Bolté’s contribution as follows: “When they are setting the experiments there is so much for them to remember that they have to follow each other about, reminding themselves what to do. One tiny thing forgotten would mean a whole nature film ruined.” For someone so important to the whole Secrets operation, Bolté received very little recognition. Image: Field and Smith, Secrets of Nature.

Kate Smith (née Ustonson, 1880-1959) worked with her husband F. Percy Smith at the couple’s studio-laboratory and home in Southgate, on the outskirts of London. Often described as a ‘truly ideal wife for a scientist’, in reality she was much more than that. The daughter of a spectacle maker, she was described in census records as a ‘spectacle glazier’ herself prior to her marriage to Smith. This technical knowledge no doubt proved useful to her when it came to assisting with her husband’s film work. Image: Science Museum Group

F. Martin Duncan (1873-1961) pioneered many of the techniques in microcinematography employed by F. Percy Smith. Duncan worked for Charles Urban making science films for popular audiences, and later became Librarian of the Zoological Society of London. He produced numerous films while working for the Zoo, many of which were purchased by British Instructional Films when Secrets of Nature was launched in the early 1920s. Image: The Bioscope, 27 May, 1909, p. 29.

H. A. Gilbert (1886-1960) was a former cricketer and a captain in the Army during the First World War, where he was wounded at Ypres. Gilbert was also a well-known naturalist who published several books and wrote articles for the magazine Sporting and Dramatic. Smith and Field wrote of him: “While he is a keen student of bird-life and has a great knowledge of the ways and habits of feathered creatures, he nearly always learns a great deal from his films, using his pictures to add to his knowledge”. Image: The Picturegoer, February 1931.

Edgar Chance (1881-1955) was an ornithologist. He possessed a large collection of birds’ eggs that resulted in his expulsion from the British Ornithologists’ Union and is now held at the Natural History Museum in Tring. His book The Cuckoo’s Secret (1922) was released in the same year as the eponymous Secrets film, demonstrating for the first time how the Cuckoo lays its eggs in other birds’ nests. Image: archive.org.

Julian Huxley (1887-1975) was a well-known biologist who collaborated with the Secrets producers on several occasions. In the 1930s, he supervised a series of educational films in biology produced by Gaumont-British Instructional. Huxley later collaborated with Walt Disney in making the True Life Adventures. His review of Field and Smith’s 1934 book Secrets of Nature can be read here. Image: Huntingdon Library.

H. R. Hewer (1903-1974) was a zoologist at Imperial College London, who specialised in the study of seal behaviour. Hewer used film in his own research, and collaborated as a scientific consultant on several Secrets. Together with Julian Huxley, he supervised G.B.I.’s Biology teaching films in the 1930s. Image: British Newspaper Archive.

Margaret Thomson (1910-2005) was a zoology graduate from New Zealand who moved to London in 1934. There, she was hired by H. Bruce Woolfe to produce a series of films on ecology, the footage of which is likely to have ended up in Secrets of Life. Later she became part of the documentary film movement, working with Realist Films before returning to New Zealand as director of the National Film Unit. Image: Julie Benjamin.

Walter Higham (1900-?) was described by Field and Smith as “an artist absorbed above everything in trying to capture for all time the passing beauty that he sees”. He worked for the Secrets team from 1922, mainly supplying ornithological footage, and won a medal from the Royal Photographic Society for his film The Bittern (1931). He was a well-respected still photographer and his book Birds in Colour (1946) was the first British bird-book to be illustrated solely with colour photographs. Image: The Bittern (1931)

W. P. Pycraft (1868-1942) was an assistant of the British zoologist E. Ray Lankester. He worked at the British Museum (Natural History), where he was Curator of Osteology, and was the author of numerous books in popular science. He is listed as a collaborator in several early Secrets of Nature films. Image: from Portrait of the Piltdown skull being examined by John Cooke, 1915. Geological Society of London.

Gladys M. Callow (1894-1977) was a schoolteacher who appeared in the Secrets film Strange Friendships in 1924. Callow appeared in the London Zoo alongside ‘her wild animal friends’, which had become accustomed to her presence. Image: British Newspaper Archive.

W. E. Hodgson (dates unknown) composed the music to the Secrets of Nature films once they made the switch to sound with Peas and Cues in 1930. In the 1920s, he was the orchestral director at the Marble Arch Pavilion, a prestigious London cinema, where he was in charge of a thirty-strong orchestra. Field and Smith wrote of Hodgson that, “‘unlike many musicians, he appreciates the fact that the musical setting is to enhance the film and not to overwhelm it”. Image: British Newspaper Archive.

Clotilde von Wyss (1871-1938) was a science educator who was consulted on several Secrets films and was a prominent figure in the ‘Nature Study’ movement in Britain. She worked at London’s Institute of Education. The producers appreciated not only her pedagogical experience, but also her detailed scientific knowledge, which was critical in making the 1936 film Wood Ants. Image: UCL Special Collections.

Victor Peers (1897-1971) provided the spoken commentary for the first two ‘talkie’ seasons of Secrets of Nature. Field wrote that he had ‘a genius for finding himself cues and was a delightfully easy person for whom to write speech’. Peers was an executive producer, and his other engagements meant that he had to abandon doing voiceovers. He would later work with Alfred Hitchcock, and became general manager of Granada Television. Image: British Newspaper Archive.

E. V. H. Emmett (1902-1971) was the voice of Secrets of Life. He was the newsreader for Gaumont-British News, and also narrated multiple feature films. His voice was the characteristic newsreel sound of the 1930s. ‘Sad, amusing, exciting, unusual, that voice always matches perfectly in tone and expression what it is describing’ (Hastings and St Leonards Observer, 21 November 1936). Image: Wikipedia.

Ludwig Koch (1881-1974) was one of the world’s first wildlife sound recorders. Arriving in England from Germany in 1935, he collaborated with Julian Huxley and Max Nicholson to produce a “song-book” of Britain’s wild birds, and also contributed recordings to the BBC. However, Koch’s recordings were also used in films, especially ornithological ones where obtaining birdsong was often a tricky business. For instance, the Secrets film Singing While They Work (1942) featured recordings of thrush, garden warbler, blackbird and nightingale. Image: Wildlife Sound Recording Society.

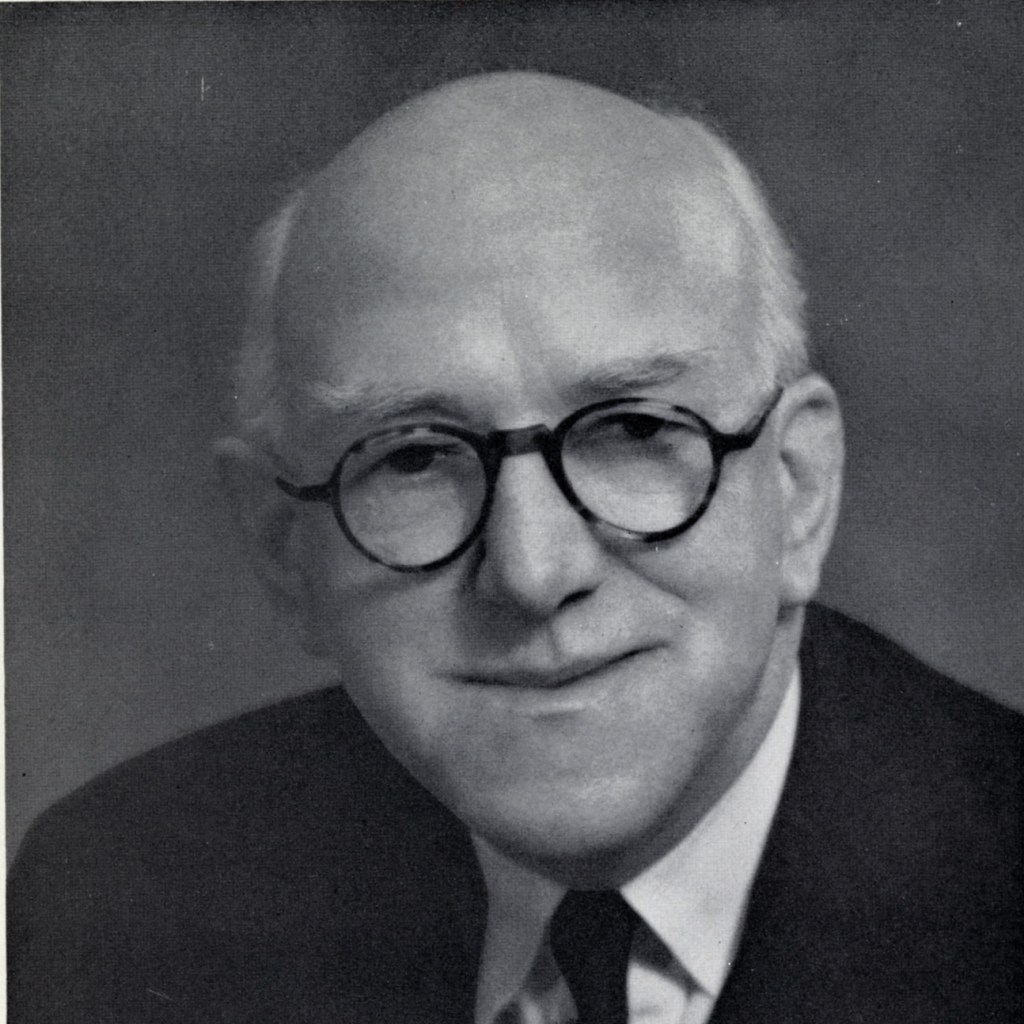

E. J. Salisbury (1886-1978) was a well-known botanist and ecologist, who taught at University College London before being appointed as director of Kew Gardens in 1943. He published several popular books, and was a major collaborator on G.B.I’s biology educational films. Image: American Philosophical Society

Winifred Cullis (1875-1956) was a scientist and energetic educator and populariser. In 1919, she became Professor of Physiology at the University of London. For the BBC, she produced a series of School Broadcasts called ‘Your Body Every Day’ in the early 1930s. Although not directly involved in the Secrets films, she collaborated with the team on a series of hygiene films for Gaumont-British Instructional in the 1930s, and also introduced a screening of nature films by G.B.I. at the 1937 Conference of Educational Associations. Image: Wikipedia.

H. Maxwell Lefroy (1877-1925) was an economic entomologist who pioneered the use of insecticides. From 1903 to 1912 he was Imperial Entomologist to the government of India, and became the first Professor of Entomology at Imperial College London in 1912. He collaborated with several early Secrets of Nature films. One of the more unusual Secrets was made under his supervision: The Story of Westminster Hall (1923) recorded Lefroy’s eradication of the death watch beetle from the old timbers in the Palace of Westminster in London. Image: Rentokil.

Peter Chalmers Mitchell (1864-1945) was a zoologist. He was Secretary of the Zoological Society of London between 1903 and 1935, when he was succeeded by Julian Huxley. He collaborated on several Secrets films, especially those filmed at the Zoo. In the early 1920s, British Instructional Films advertised themselves as ‘sole agents’ to the Zoological society, something which Chalmers Mitchell is likely to have arranged. In 1912 he published ‘The Childhood of Animals’. Image: Zoological Society of London

Madeline Munro (1885-1974) was a science educator who sat on the British Film Institute’s science committee and wrote reviews of scientific films in the Monthly Film Bulletin. Originally trained as a palaeontologist, she received her degree in Geology from the University of London in 1907. Munro was also consulted in the production of school broadcasts in nature study and science for the BBC.

Harold Mease Lomas (1873-1926) was born in Clifton, Bristol and trained as a chemist. A keen hunter, he published several hunting books illustrated with photographs, and approached Charles Urban with the idea of making hunting films in 1902. He made several filming trips to North Borneo, with Urban releasing a number of films based on Lomas’s footage. Lomas joined British Instructional Films in 1921, and filmed several films for the Secrets of Nature series at the UK Marine Biological Station in Plymouth. He was a member of the Royal Photographic Society’s Kinematograph Group.Image: The Royal Photographic Society Journal, Vol. 124, p. 197.

Charles D. Head (? – 1938) was a specialist cameraman who worked closely with the Secrets team. He was described by Field and Smith as ‘like an eighteenth-century diarist, bent on recording the simple scenes of everyday life that surround him’. According to the Bioscope, His film The Merlin (1930) broke a record for shorts by being exhibited at the Marble Arch Pavilion 312 consecutive times.

C. W. R Knight (1884-1957) was a well-known falconer, photographer and filmmaker. He is often referred to as ‘Captain’, referring to his service in the First World War. Knight was an enthusiastic lecturer, often appearing alongside his pet golden eagle, known as Mr. Ramshaw. Knight and Mr. Ramshaw would appear in Powell & Pressburger’s film I Know Where I’m Going (1945), and he also served as falconry adviser in Alexander Korda’s The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933). Knight is credited on a couple of early Secrets films, including The Sparrow-Hawk (1922) and The Rook (1922), although his most popular film, The Filming of the Golden Eagle (1927), was not part of the series. You can read a fuller biography here. Image: British Newspaper Archive.

Geoffrey Barkas (1896-1979) was a filmmaker and camouflage expert. He is credited on some of the earliest Secrets of Nature films, including The Battle of the Ants (1922) and Marine Parade (1923). He also filmed made a film of the first airplane flight over Mt. Everest in 1933. Image: First over Everest: the Houston-Mount Everest expedition (1933)

Frank Goodliffe (1900-?) was a cameraman who specialised in biological subjects and cinemicrography, and produced footage for both the Secrets series and the G.B.I educational films. One of the highlights of his career was his use of fast-motion images to observe meteorological phenomena. Later he was the Films Officer to the Public Relations Department of the colonial government in Southern Rhodesia. He was Chairman and Director of Productions of ‘Science Films’, a company established by Norman MacQueen and H. Bruce Woolfe.

Jack Parker (1885-?) was a professional cameraman who worked with the Secrets team. He was involved in the series from its inception, and working also on other B.I.F films including The Battles of The Coronel and Falkland Islands (1927).

George Pocknall (1880-1940) was principal cameraman for G.B.I., and worked with H. Bruce Woolfe from the early 1920s. He collaborated with some of the most influential documentary filmmakers of the interwar period, including Paul Rotha and Brian Salt. Rotha, in Documentary Diary, wrote that he was “unmatched in his shooting of exteriors”. His obituary in Sight and Sound noted that “in addition to being a first class cameraman, he was an extremely efficient scientific instrument maker”.

Oswald Stoll (1880-1940) was the owner of British Instructional Films between 1924 and 1927, when he sold the company to A. F. Bundy. Stoll was an Australian-born theatre impresario, who owned the Empire and Colosseum theatre franchises, as well as the film production company Stoll Pictures, which was a key producer of silent films. Stoll also established the company Visual Education Ltd. alongside James Marchant in the late 1920s, which also focussed on the production of educational films and collaborated with some of the same individuals as the Secrets, including E. J. Salisbury and Charles Head. Image: British Newspaper Archive.